Give the people what they want

You gotta give the people what they want

The more they get, the more they need

And every time they get harder and harder to please

From “Give the People What They Want” by the Kinks

It was exciting waiting in line for The Fellowship of the Ring, shiny ticket stub in hand. I was in Philadelphia at the time. The city was buzzing with construction. New grocery stores. New apartment buildings. New movie theaters. New. Fresh. Shiny. Words to describe the spirit of the time. As luck (and production value) would have it, the movie was incredible. It had magic and swords and fire, everything you’d expect Tolkien’s words on a screen to look like.

Before The Fellowship of the Ring, fantasy was relegated to the edges of cinema. Production houses considered movies like the NeverEnding Story or Willow oddball, niches mainstream audiences would never care about. Unlike its somewhat more respected cousin in science fiction, fantasy never seemed to receive the lauded red carpet treatment. The success of Fellowship was a seachange. Film critics were finally discussing fantasy, production houses were eager to produce more of it.

But something changed over the years. I can’t pinpoint exactly when. Maybe it was seeing other fantasy adaptations fall apart after a season or two on TV. Maybe it was the third Spiderman reboot or the fifth Batman reboot. Or maybe it was the deluge of adaptations jammed into the venerated three-act structure, each differing in some minor fashion.

I felt a creeping dread. A dread for the inevitable mainstream response to the works: that they’d be watered down, that they’d dictate how storytelling would look in the future. I think what I dreaded the most, though, was the realization we were heading into an era of narrative monopolies.

Monopolies and Competitive Markets

We’re familiar with traditional monopolies in business. One or a handful of companies create moats in their industry, so customers simply can’t leave. Perhaps it's out of love for the product, or simply because there is no alternative for customers. Investors love monopolies because of these moats they create. For simplicity’s sake, we can say these moats allow monopolies to control pricing power, siphoning profits back into its endeavor. This is the opposite of competitive markets, which allow for multiple entities to compete on pricing, each trying to edge each other out in a perceived race to the bottom.

In his book Zero to One, investor Peter Thiel writes about the dynamic between competitive markets and monopolies:

“Every firm in a competitive market is undifferentiated and sells the same homogeneous products. Since no firm has any market power, they must all sell at whatever price the market determines. If there is money to be made, new firms will enter the market, increase supply, drive prices down, and thereby eliminate the profits that attracted them in the first place. If too many firms enter the market, they’ll suffer losses, some will fold, and prices will rise back to sustainable levels. Under perfect competition, in the long run no company makes an economic profit.”

“The opposite of perfect competition is monopoly. Whereas a competitive firm must sell at the market price, a monopoly owns its market, so it can set its own prices. Since it has no competition, it produces at the quantity and price combination that maximizes its profits.”

It’s callous, vulgar even, to think about books and movies as widgets. After all, who wants to compare a piece of artistic work to say soap or shampoo? But, to the board rooms of production houses, they are similar. The bottom line is profit.

To maximize their profits, monopolies create moats around IP. Think about the Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Marvel, DC Universes. Consider the sheer weight of material that has been produced around them: comics, books, movies, graphic novels that adapt books, movies that adapt comics, T-shirts, toys, lunchboxes, Lego sets, mugs. Type ‘R2D2’ into Amazon and take a look at what comes up.

Even my Spotify has a lightsaber theme when the Star Wars theme plays.

And of course there are the simultaneously lauded and dreaded movie sequels. I’m looking at this list of top grossing films of all time. Let’s consider some of the names. An Avengers movie shows up three times in the top 10. Star Wars of course. A Jurassic World movie shows up twice in the top 20. Furious 7 . . .

I think you get my point.

The box office numbers themselves are gigantic. We’re talking billions of dollars per movie, multi-billions per franchise.

Give The People What They Want

Now, it’s likely that producers will claim they only, like in the Kinks’ song, give the audiences what the audiences want. We have heard this before from the news media justifying coverage of fearful over hopeful stories or pharmaceutical companies arguing that people want television ads for drugs. These are both industries that rely on repeated purchases of similar goods.

Narrative monopolies suffer from this too. At the end of the day, the numbers drive the decision making. For example, film adaptations make 53% more than their counterparts. Even if a producer wanted to make a new film, it’s likely they’ll choose from stories that already exist. It takes a brave producer to attempt to make a movie, particularly a blockbuster, that doesn’t fit a known mold.

These moats are antithetical to creative regimes, where ideas come to life through experimentation, breathing fresh life into our shared experience. A narrative monopoly’s moat eventually becomes stale like an old pond infested with mosquito eggs. Repetitive adaptations of ideas whose sole purpose is to sell more widgets cause creativity to fester. There is no incentive, no impetus to push for growth. The idea-as-a-widget becomes a commodity which can get a fresh wrapping to be sold as the next shiny new object.

As these moats grow, and the narrative monopolies strengthen, they’ll continue churning out shiny new, yet ultimately undifferentiated objects. It will become harder for new ideas to emerge, new authors to emerge, and of course, new stories to be told. And if we are the product of the stories we consume, and if our stories are stale, then our growth stalls as well.

Storytellers As Tricksters

In his excellent essay, Trickster in a Suit of Lights, Michael Chabon writes about pushing boundaries for short story tellers.

But among our most interesting writers of literary short stories today one finds a growing number — Kelly Link, Elizabeth Hand, Aimee Bender, Jonathan Lethem, Benjamin Rosenbaum — working the boundary: “sometimes drawing the line,” as Hyde writes of Trickster, “sometimes crossing it, sometimes erasing or moving it, but always there,” in the borderlands among regions on the map of fiction. Because Trickster is looking to stir things up, to scramble the conventions, to undo history and received notions of what is art and what is not, to sing for his supper, to find and lose himself in the act of entertaining. Trickster haunts the boundary lines, the margins, the secret shelves between the sections in the bookstore. And that is where, if it wants to renew itself in the way that the novel has done so often in its long history, the short story must, inevitably, go.

These boundaries we need to push are interesting to me. When we say a particular story sits squarely in fantasy or science fiction, we have a model for what that story will be like. Production houses take advantage of these boundaries for purposes of marketing. A comic book movie is a three-act structure with a super-powered protagonist taking on a villain. There’s no real room to push that boundary. Audiences won’t like it. They expect to see a caped crusader. They may even get angry that their expectations were subverted.

I can say this with certainty: any time I’ve been blown away by a book or film, and felt that it allowed me to think about something in an entirely new way, it’s been from something new, something fresh, something different from stories that came before it.

Some of my favorite stories are ones that shove the perceived borders, meld orthogonal ideas together in a congruent way. “Safety Not Guaranteed” is an outstanding film about a magazine intern investigating a strange classified ad that reads as following:

Wanted: Somebody to go back in time with me. This is not a joke. P.O. Box 91 Ocean View, WA 99393. You'll get paid after we get back. Must bring your own weapons. I have only done this once before. SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED.

Its genre is science fiction, but there are no traditional villains, no spaceships, or heroes in the classical sense. It’s a quiet, personal film which involves time travel, and it’s funny and touching. It’s astonishing that a movie with a $750,000 budget can have a powerful effect compared to blockbusters with multi-million dollar budgets.

Borders need to be pushed by their very existence, and when they are, we have a chance at seeing our world differently, a chance at wrinkling our brains some more. The flipside, of course, is that the more we sell stories that are nothing more than tributaries of mass-produced moats, all we have are the same stories we’ve already seen. Encapsulation of narrative monopolies produces commodified goods. Repeated consumption of these commodities makes us rigid. If we don’t push boundaries, by definition, we stagnate.

The most damning thing about modern entertainment is that our tricksters–those who should be pushing boundaries–are executives and data analysts at production houses. Their claim “because this was successful before, the sequel or reboot will be successful again” translates to “because this made us billions before, the sequel or reboot will make us billions again.” Notwithstanding this miserable approach to entertainment, it contains the spurious assumption that this is precisely what all viewers want.

If all we give consumers is the familiar, then we are no longer storytellers, no longer tricksters. We’re simply mouthpieces for narrative monopolies, tacky over-dressed salesmen for the next shiny widget, running in place in two dimensions, when we could be flying in three.

Some publication news

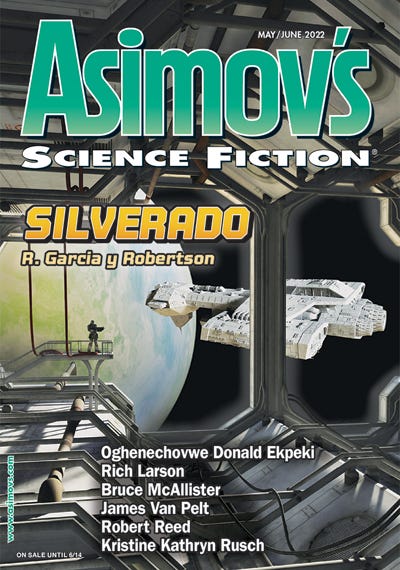

In some exciting news, my short story “The Abacus and the Infinite Vessel” will be in Asimov's May/June 2022 issue. It’s "hitting the newsstands," as they say, on April 19. I’ve been reading Asimov’s for decades, and I’m thrilled to have one of my stories appear on their pages. The story's about a Tamil mother and daughter immigrating to a Mars colony. Please pick up a copy if you can. Would love the support!

Until next time.